http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/mo...o_die_for.html

Pete Kennedy just wanted to be buff, but in the end,

he paid ultimate price for using steroids

BY WAYNE COFFEY

DAILY NEWS SPORTS WRITER

Sunday, March 25th 2007, 4:00 AM

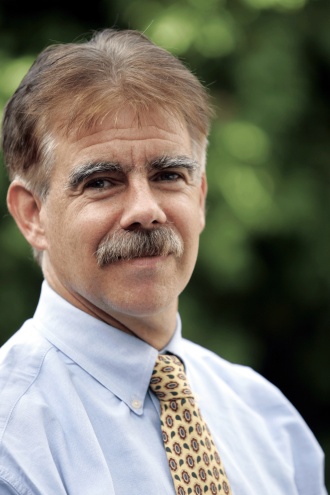

Pete Kennedy

Pete Kennedy with his sister Jamie at Albany Medical center days before he died from steroid-related damage to his heart and kidneys.

EAST BERNE, N.Y. - Long before his muscles got big and his organs shut down, Pete Kennedy was just a country kid who loved to tinker. In the garage next to the little blue house on a hilltop he shared with his mother and sister, he would spend hours taking machines apart, and putting them back together.

His mother still remembers the time he came home with a bushel basket full of dirt bike parts, when he was 12. Two weeks later, Pete was riding the thing up and down Main St.

"He could build anything," Barbara Kennedy says of her son. "You could give him something that didn't work, and he would fix it. He would fix my tractor, my car, fix my aunt's vehicles. Friends would call and say, 'Pete, I have a problem,' and he'd say, 'Bring it over.'"

There will be no more automotive reclamation jobs for Pete Kennedy, no more wizardry with his wrenches. He died in the intensive-care unit of Albany Medical Center in the early hours of Friday morning, three weeks before his 28th birthday, three weeks to the day after he was hospitalized with what his mother thought was a heavy cold. Barb Kennedy was supposed to pick him up the next morning, never imagining the heartache to come; that her only son would have his healthy body ravaged by steroid use, that he would become the nation's latest chemically enhanced tragedy - a young man who just wanted to be big and buff, and wound up in the ground.

Barbara Kennedy found out with a 4 a.m. phone call from the hospital.

"I pray that no other mother ever has to go through this," she says.

Pete Kennedy was born and raised here, in the hill country southwest of Albany, a community (pop. 1,843) where people leave their houses unlocked and their keys in the ignition. Pete never played team sports; he just rode his four-wheeler and snowmobile, and lifted lots of bales of hay. He was a sinewy 6-1, 162-pound farmboy who worked for a glass manufacturer and had a bedroom done completely in John Deere, from clock to sheets.

Could there be a more improbable person to intersect with the burgeoning investigation into Internet steroid trafficking being conducted by David Soares, the Albany County district attorney? A less likely face of an orbit of steroid use that has nothing to do with home-run records or Olympic gold medals - but rather with a simple desire to bulk up?

While there is no evidence linking Kennedy's supply of Nandrolone and testosterone to the alleged steroid distribution ring - a widespread web of doctors, pharmacies and wellness centers that has already implicated several athletes - that Soares is investigating, authorities view the case as a heart-rending reminder of the prevalence, and the perils, of anabolic steroids, particularly those sold on the black market.

"Steroid use has been a drug of denial for many years," says John L. Lestini Jr., director of the National Steroid Research Center. "People say, 'It's an athlete's problem, let them solve it.' Well, it's not an athlete's problem. It's a widespread public health problem that we can no longer ignore."

Gary Wadler, a professor at the NYU School of Medicine and member of the World Anti-Doping Agency, agrees. He says much of the U.S. supply of steroids and human growth hormone comes from Mexico and the Far East, from unknown sources with, quite likely, nonexistent regulatory standards.

"If these drugs are pure, they are dangerous," Wadler says. "If you have no idea what you're swallowing or injecting, it becomes true Russian Roulette. The attitude in America is, 'They wouldn't sell it if weren't safe. They wouldn't sell it if weren't pure. They wouldn't sell it if it didn't work.' The problem is we're not dealing with drugs from the regular marketplace."

* * *

As far as Barb Kennedy can tell, the trouble started last April, after Pete got his second DWI. He was on his way home from Lake George. He'd had some Miller Lites at a bar, and refused the Breathlyzer test. His license was suspended. His probation mandated that he couldn't drink, couldn't join his buddies for Thirsty Thursdays at his favorite bar down the street, the Maple Inn. He felt a void. He opted to fill it by working out. He cleaned out the basement of the garage and set up an impressive array of weights, punching bags and fitness equipment.

By last summer, Pete Kennedy was lifting up to four hours a day, five days a week. He was constantly drinking power shakes and other concoctions. He spent $300 monthly at GNC, according to his sister, Jamie, 22. When he lifted, he had his heavy metal music blaring - "Anger music," he called it - and pushed himself to almost complete exhaustion.

"Aren't you overdoing it?" his mother would ask.

"No, I'm fine," Pete would say, before cranking up the music to drown out her voice.

"The gym became his crutch," Barb says.

For years Pete and Barb wore interchangeable jeans, waist 29, but that changed. His arms began to bulge with slabs of muscle, and his neck and chest thickened and hardened, as his weight increased to 170, 180, 190 - all the way to 215. Jamie noticed his jawline becoming more pronounced - a common side effect of HGH - and Pete's girlfriend said his back had developed severe acne - a condition that often accompanies steroid use.

Seeing him every day, Barb was slow to notice any changes at all, until Pete needed new pairs of size-34 jeans. He was becoming increasingly impatient and sometimes irritable, she realized. She asked him straight out if he was using steroids. Pete said no. She brought it up several other times. He was emphatic, just as he was when Jamie asked him about it.

"I'd never do that. I would never stick a needle inside me," he said.

Barb Kennedy is a dark-haired, 47-year-old woman with the sturdy grip and down-home bearing of a person who has spent a lifetime around the farm. She raises quarter horses and holds down three other jobs - waitress, short-order cook and an aide in a veterinary clinic. She knows when horses have been pharmacologically enhanced.

"I can pick a horse out in the crowd with steroids, but I couldn't pick my son out," she says. Sitting in the hospital cafeteria last week, amid another 10-hour day at her son's bedside, she blamed herself for not going at Pete harder.

"I wish I'd called him a liar and did the thing that parents don't like to do - searched his room," she says.

That search was belatedly conducted three weeks ago, Pete already in St. Peter's Hospital after complaining of a persistent cold, extreme fatigue and shortness of breath. Within hours of his admission, his kidneys shut down, his liver began to fail and his heart was enlarged. His blood was full of toxins. Doctors induced a coma as they figured out how to proceed. They asked Barb Kennedy if her son took steroids. Just before Pete was transferred to Albany Medical Center, Jamie got a call from a friend of Pete's. The friend said that awhile back Pete had asked where he could get hold of steroids. Jamie hung up and went into Pete's room. She looked everywhere. In the bottom of the closet she found a fireproof safe. She went to the desk and got the keys. She opened the safe. Inside it was a plastic bag with eight 30-milliliter bottles, four brown and four clear. "Testosterone," it said on the brown ones, next to a homemade label with a caricature of an overly muscled man.

Jamie began to sob. "My heart just dropped to the floor," she says.

* * *

Nobody knows for sure when Pete Kennedy started taking steroids, or how much he was taking. Linn Goldberg, M.D., a professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University and a leading researcher of youth steroid use, says it's not uncommon for "an average steroid user to take up to 100 times the normal level of testosterone."

State drug-enforcement investigators, working with DA Soares' office, are probing the black-market source where Pete Kennedy got his drugs. At 4:30 Friday morning, right after Barb Kennedy got the worst call of her life, she made a call herself.

"Go get the sons of bitches," she told investigators.

The terrible irony is that a day before his death, Pete Kennedy had had his best day in three weeks. He was taken off the respirator, and began to do some breathing on his own. His eyes opened and he seemed a bit more alert. Pete and Jamie are extraordinarily close - he always called her "Kid." Jamie asked him if he could say, "Hey, Kid." Slowly, almost inaudibly, Pete repeated his sister's words. Hours later, his breathing became labored and his heart began to race. The respirator was reinserted, but his heart finally gave out. "He fought hard," Jamie says. "I just don't think he could fight any longer."

Throughout the ordeal, the Kennedy family has been astounded at people's kindness. At the restaurant where Barb waitresses, two couples recently had a $160 dinner, and left $400. Barb ran after them and told them they had made a mistake. "No, we didn't," one of the men said. Food keeps showing up in Barb's refrigerator. People drop by with money here and there, to help pay for the $93 fillups for Barb's truck, and to help her cover the $479 monthly payments on Pete's beloved Ford F-250 pickup. A fellow farmer gave her $400 for a month's feed for her horses, and there is an upcoming benefit spaghetti dinner at the East Berne firehouse, followed by another at the Maple Inn. They are much more pleasant things to think about than the persons who sold the eight bottles of steroids that made their way inside Pete Kennedy's safe. "If a hillbilly on top of a mountain can get a hold of it, then it can get anywhere," Jamie says.

Over the last quarter-century, as steroids have become as much of a sports-world staple as standings and shattered home-run records, some have depicted their distribution and use as a victimless crime - not worthy of prosecutors' time. If some cartoon-character linebacker or slugger wants to take such a risk, what's the big deal? The NSRC's Lestini scoffs at that notion, and so does Wadler, who sees steroid trafficking as "every bit the money-driven enterprise that the cocaine and heroin businesses are." Steroid use routinely comes bundled with financial, familial and psychological wreckage, experts say.

Barbara Kennedy never figured she'd be wei***ng in on this, but she never imagined living through the hell she's lived through the last three weeks. She has bills to pay. She has a son to bury. She has a life she must try to carry on, without devouring herself with regret about what she might've done differently. Don't waste your time talking to her about victimless crime.

"I have proof it's not true," Barbara Kennedy says. "And the proof is seeing a mother watch her son die and not be able to do anything about it.”

Daily News Specials

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote