The Protein Bible

By: John Berardi

The issue of protein intake has been a source of much controversy among medical doctors, registered dieticians, nutritionists, scientific researchers and, of course, all kinds of athletes.

It is my strong opinion that "the great protein debate" was resolved in the 90's when numerous well controlled research studies demonstrated that both strength and endurance athletes needed more protein than had been predicted by energy equations and by simple nitrogen loss measures. Actually, the research studies have become abundant.

Athletes universally believe that high-protein diets increase performance and or muscle mass. Although this could just be a strong placebo effect, I think there may be some validity to these claims. First, the high protein intakes could lead to a strong positive nitrogen status which, when combined with rigorous strength training, may potentiate the growth process. Secondly, there are several other nutrients in high protein foods that could enhance performance and/or hypertrophy. Although there are few data on this second point, some obvious nutrient possibilities include creatine, specific amino acids (perhaps one or several of the BCAAs), conjugated linoleic acid, and/or some other unknown growth factor(s) that remain(s) to be determined [Peter W.R. Lemon, Ph.D. Nutrition and Exercise Laboratory, University of Western Ontario, ON, Canada].

Protein Need vs. Optimal Protein Intake

Conservative research studies are designed to figure out how much protein is needed to prevent deficiency. While a deficiency will probably lead to a loss in muscle mass and/or a loss in athletic performance, eating just enough protein to prevent a deficiency may not exactly lead to the best possible performance.

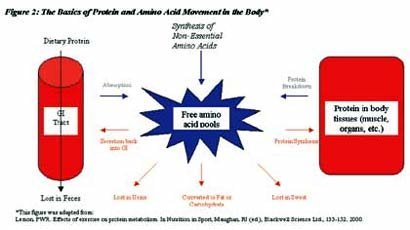

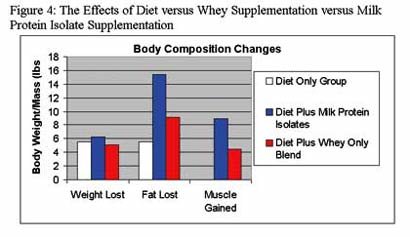

Numerous well - controlled research studies have been done to determine the exact amount of protein needed in athletes and weightlifters to achieve nitrogen balance. Nitrogen balance occurs when the amount of protein that goes into the body is equal to the amount that leaves the body (through urine, sweat, feces, etc) [Peter Lemon, Ph.D., and Mark Tarnopolsky, M.D., Ph.D.,. have conducted some of the best research in this area [Lemon et al. 1981, Lemon, 1997, Tarnopolsky et al. 1988, Tarnopolsky et al. 1992]. The results of these studies have demonstrated that both endurance and strength athletes often require more than double the protein of the average sedentary person (see Figure 1)].

In Figure 1, different protein intakes were compared and the resulting nitrogen balances were reported. These data tell us that endurance athletes need at least 0.54-0.64g/lb. while strength athletes need at least 0.77-0.82g/lb. to achieve nitrogen balance.

Recall that the recommended daily allowance (RDA) for protein has been set at ONLY 0.36g/lb. (0.8g/kg).

Many athletes are convinced that even higher levels of protein consumption beyond what Drs. Lemon and Tarnopolsky recommend will definitely impact muscle mass if not performance!

A 200-lb. strength athlete who desires to maintain body weight and prevent protein deficiency should eat approximately 154-164g of protein per day. Eating enough total calories is important as well, because protein needs are affected by many factors including: the type of training that you do (endurance vs. strength), your training history and your total calorie intake. Basically the fewer calories you are eating, the more protein your body needs to stay in balance or to achieve positive status [Lemon, 1995].

Some people have speculated that testosterone and anabolic steroid users will benefit from increased protein intake above the 1.5-2.0g/kg that Dr. Peter Lemon recommends for natural weightlifters. I certainly believe it's a distinct possibility that some supplements require a protein intake beyond current recommendations to exert noticeable effects. Any drugs or supplements that may have an impact on anabolism may require a higher protein intake [Tim Ziegenfuss, Ph.D. Human Nutrition Laboratory, Kent State University, Ohio, USA. Director of Research and Education, Phoenix Laboratories, New York, USA].

Seeking Maximum Muscle Mass

But what athletes want maximum muscle mass? Again, looking at Figure 1, it is evident that increased protein intakes above those needed to prevent deficiency will lead to a greater positive nitrogen status. Although at these high levels of protein intake, both total body protein synthesis and protein breakdown are increased, the amount of protein that stays in the body is usually higher at the higher protein intakes (up to a point).

Lemon has suggested that intakes over 0.82g/lb.-0.90g/lb. (1.8-2.0g/kg) may not be beneficial despite the apparent increases in positive nitrogen status. He believes that a ceiling may exist that prevents more muscle gain when eating above this level [Lemon, 2000]. One of the studies supported this in that although nitrogen balance was greater in subjects consuming 1.2g/lb. (2.6g/kg) vs. those consuming less protein for an 8-week weight training period, the higher protein group was no bigger [Tarnopolsky et al. 1992]. However, maybe this was due to the short duration of the study rather than the inability of higher protein to increase muscle mass.

Lemon tends to agree in at least one case, and suggests that when using anabolic agents (i.e. growth hormone, testosterone, etc), a high-protein intake may be necessary to maximize muscle gains [Bhasin et al. 1996, Lemon, 2000].

It's well accepted in the weight lifting community that during anabolic steroid use, protein intake should be around 2g/lb. (4.4g/kg). (So a 200-lb., hard training bodybuilder also using AS and GH might use 400 grams of protein a day)!

Going back to our 200-lb. natural strength athlete looking to increase muscle mass, I suggest that he/she might benefit from 182g of protein per day. The research is unclear whether more protein may further produce muscle gains, however, anabolic steroids theoretically increase nitrogen retention and, therefore, protein requirements.

Protein Intake: Performance Or Mass?

Athletic performance is dependent on many factors including skill level, conditioning, and team or individual strategies. Certainly, lack of nourishment will decrease performance but eating an excess of protein, carbohydrate, or fat might not increase performance (unless you are a strength and power athlete). Studies examining whether very high protein intakes can enhance a variety of athletic performance have not been promising [Lemon, 2000].

The bottom line is that it appears better to over-eat than to under-eat protein when someone's trying to add muscle mass while keeping body fat off. Excess protein calories are not as likely to be stored as body fat compared to carbs and most fats. This is because the metabolism and processing of protein is energy costly endeavor in that it's more thermogenic and activates hormones that help with fat loss [Lonnie Lowery, PhD. Human Nutrition Laboratory, Kent State University, Ohio, USA].

Carbohydrates make up the predominant energy source for most athletic activities. In general, only a small amount of protein is burned for energy during exercise. In fact where normal diets are consumed, it is only significant (5-15% of total calories burned) for long duration endurance training [Dohm et al. 1982, Lemon and Mullin 1980, Lemon et al. 1983, Yarasheski and Lemon, 1983]. High levels of blood or muscle protein don't immediately contribute to the energy needs of exercise modes.

However, while protein is not a great pre-game meal, athletes usually follow year-round intense training programs. Recovery from these intense training sessions is necessary to see continual progress. Therefore, from a recovery perspective, protein intake may be as important, or more so, to the athlete as the other macronutrients.

Will a high protein diet increase muscle mass? Yes. But, will this increase performance? Since many athletes believe in the power of protein to increase muscle mass, more studies need to be done. However it only stands to reason that if muscle mass is increased due to long-term high protein intakes, athletes involved in strength and power sports will undoubtedly receive a benefit over time.

Benefits Of Increased Protein Beyond Athletic Performance

While high protein diets may not necessarily improve athletic performance (beyond recovery considerations) and it's nor proven that protein above 0.82g/lb. (2g/kg) will increase muscle mass, are there any other benefits of a relatively high protein intake? I think the answer to this question is yes.

Protein and Metabolic Rate

Protein intake may positively affect body composition. Since all food requires metabolic processing, all macronutrients increase metabolism. However, the metabolic increases seen when eating protein are double those seen when eating carbohydrates or fat. Therefore a high protein intake may in fact be thermogenic and may lead to increased calorie burning and fat loss.

During dieting, this may enhance calorie expenditure and therefore the rate of fat loss [Blacklevin et al. 1975, Ballor and Poehllman 1994, Skov et al. 1999, Alford et al. 1990]. As I said above, more protein is needed on a low calorie diet anyway; especially when working out. During overeating in an attempt to gain muscle, although higher protein intake may not be needed for positive nitrogen status, it's likely better to eat excess protein rather than carbohydrates or fats. Since overeating leads to both some muscle and some fat gain, eating more calories as protein may lead to more lean weight and smaller gains in fat weight.

Did you know that eating protein might increase your metabolic rate and nutrient balance? By virtue of this phenomenon, a higher protein diet may contribute to body fat losses. Since protein foods require more "metabolic processing" than carbohydrates and fat it only stands to reason that the metabolic increases seen when eating protein would be higher than those seen when eating fat or carbohydrate. In fact, several research investigations have shown just that. The metabolic increase seen with eating protein is just about double that of eating carbohydrates or fats [Welle et al. 1981, Robinson et al. 1990, Nair et al. 1983].

Protein and Hormones

In addition to the calorie burning effects of protein, higher protein intakes can increase the release of the hormone glucagon from the pancreas [Guntiak et al. 1986, Linn et al. 2000)]. The hormone insulin prevents fat loss from adipose (fat) tissue, but glucagon is responsible for reversing this effect [Yamauchi et al. 1988]. Glucagon also does a nice job of decreasing the enzymes responsible for making fats and building up the fat stores in the liver and in the fat cells [Girard et al. 1994].

So again, higher protein intakes may lead to losses in body fat due to the thermogenic effects as well as the hormonal effects of eating protein. During dieting, this may lead to a greater rate of fat loss [Blacklevin et al. 1975, Ballor and Poehllman 1994, Skov et al. 1999, Alford et al. 1990]. And, during overfeeding, it may lead to a smaller increase in fat mass relative to lean mass gains.

Additionally, in applicable human studies, protein and branched-chain amino acid supplements have been shown to increase the IGF-1 response to eating and to exercise [Kraemer et al. 1998, Thissen et al. 1994, and Carli et al. 1992]. Therefore both protein and calorie intake may be responsible for raising IGF-1 levels. Since IGF-1 can regulate the muscle growth [Adams 1998], I believe that a high protein intake may assist in muscular development.

Protein and Cardiovascular Disease Risk

Finally, increasing the percentage of protein in the diet while decreasing the percentage of carbohydrates and fats may have some real health advantages. Increasing protein intake from 11% to 23% can lead to very favorable changes in blood lipids and cardiovascular disease risk.

So, there may be some real health and body composition benefits to higher (even "excessive") protein intakes. More research on these topics is needed but until this research is done, the reports of hundreds of athletes, bodybuilders, and weightlifters have confirmed my speculation.

We have data showing that increasing protein intake from about 10 to 20% while decreasing carbohydrate intake from 55 to 45% (with fats kept constant at 35%) can lead to favorable changes in blood lipids. However, with athletes, increasing protein to levels higher than 20% might not offer much more benefit in terms of blood lipids and may actually decrease performance since either carbohydrate and/or fat would have to be reduced in order to do so. For the majority of athletes, since carbohydrates and fats are essential for athletic performance, I would not recommend decreasing either in favor of more protein [Len Piche, Ph.D, RD. Nutrition Program, Brescha College, University of Western Ontario, Ontario, CA].

Safety of A High-Protein Diet

In the previous section I suggested that not only a high protein intake, but also an excess protein intake might have some benefit to those interested in changing body composition and decreasing cardiovascular disease risks. Again, an important distinction has to be made. High protein diets aren't necessarily in excess. In fact, according to the data discussed earlier, high protein diets in athletes are just enough to get these individuals to nitrogen balance. So this isn't an excess of protein at all!

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote